Chapter 19: Our “Leap Day”: what is it for?

You may have asked yourself at some stage in your life, “How can our calendar possibly have an integer value of 365 days (or 366 days on a leap year) whereas, on the other hand, we are told that one year lasts ca. 365.25 days (i.e. 365 days + 6 hours?)”

Does this mean that, from one year to the next, Earth ends up skewed by 1/4 of a rotation, or 90°?

Of course not. Yet, everyone knows that we add 1 day every 4 years in order to get a 4-year-sequence of 365 + 365 + 365 + 366 = 1461/4 = 365.25 (or more precisely, 365.2425 - as defined by the Gregorian calendar - some leap years being periodically skipped). Here are some explanations for the (variable) 4-year occurrence of February 29: “February 29” from Wikipedia.

“In the Gregorian calendar, years that are divisible by 100, but not by 400, do not contain a leap day. Thus, 1700, 1800, and 1900 did not contain a leap day; neither will 2100, 2200, and 2300. Conversely, 1600 and 2000 did and 2400 will.”

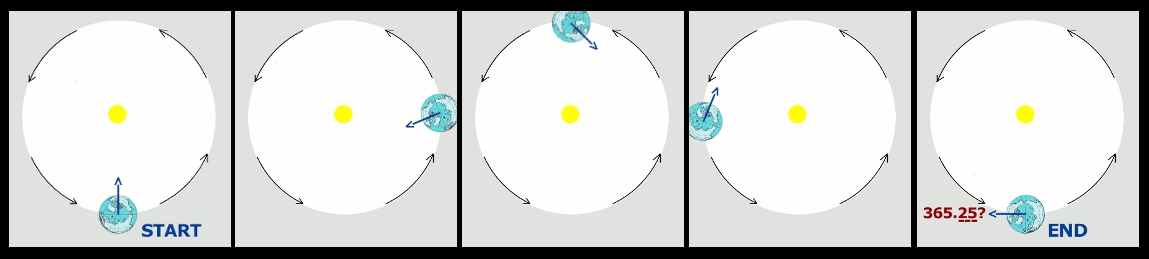

My below sequence shows ad absurdum the implication of the well-known notion that “a year actually lasts for 365.25 days”.

Here follows an extract from a charmingly-illustrated book titled "Sun, Moon & Earth" (1999) by Robin Heath.

"The solar year is 365.242 days long, practically 365. People who haven’t ever thought the matter through will often tell you there are 365 “and a quarter” days in the year, but one cannot ever experience a quarter day in isolation. Days come in packets of one, and 365 of these make up the year, except that every fourth year an extra day slips in to make it 366. At high latitudes, consecutive sunrises around the equinoxes are spaced more than the Sun’s diameter apart (five sunrises shown opposite, top ). However, each year the vernal equinox sunrise will appear from a slightly different position on the horizon — about one quarter of a degree. During three years of observation, the Sun appears to rise to the left of the original alignment until, in the fourth leap year, it rises once more very close to the original position, the tally for the year becoming 366 days. This accounts for the “quarter day" and is the basis for the additional intercalary day, February 29." Sun, Moon & Earth - by Robin Heath

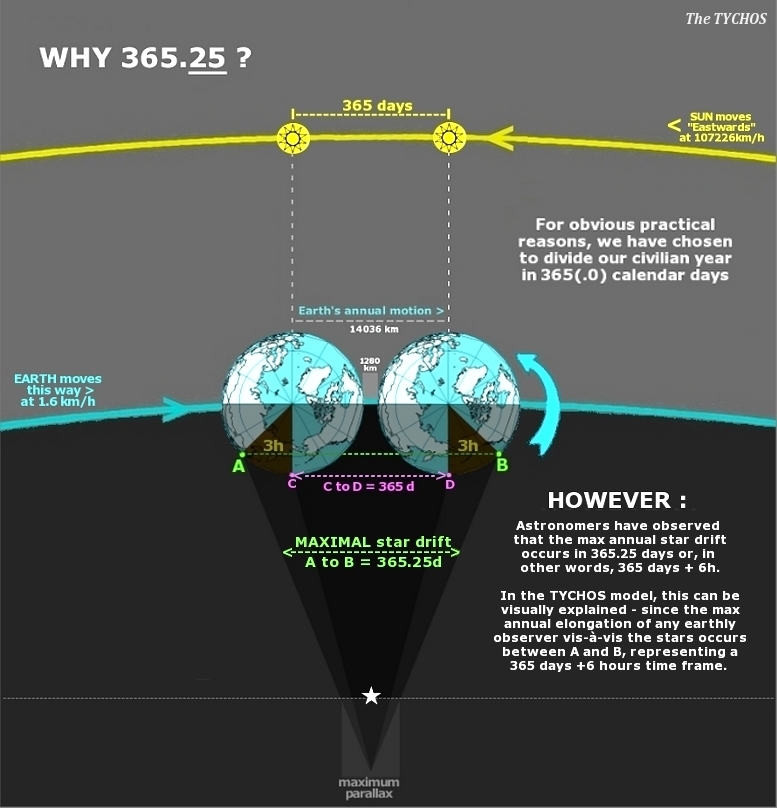

Obviously, we do not end up skewed by 6 hours at the completion of a year. Thus, we may legitimately ask ourselves:“Where do these 6 hours come from?” Can the Copernican model account for them, and can the reason for their existence be visually illustrated in a heliocentric graphic? The short answer to this last question is: No. On the other hand, the TYCHOS model can illustrate the probable motive for astronomers to have stipulated that a year lasts for about 6 hours (or ¼ of a day) more than 365 integer days.

Astronomers have observed over the centuries that the maximal annual displacement of a given star on the ecliptic (currently 'heliocentrically-estimated' at 50.3” per year) occurs between point “A” and point “B” (as marked in my above graphic). So, every year, 6 hours are considered to be “lost in space”. Therefore, they have concluded that “one sidereal year lasts for 365.25 days” (or more precisely 365.25636 days).

However, the Wikipedia’s entry on the “Sothic cycle” provides us with this piece of information :

“The Sidereal year of 365.25636 days is only valid for stars on the ecliptic (the apparent path of the sun across the sky).”

This of course goes to support the notion (illustrated in my above graphic) that the width of the Earth's diameter plays a role in the determination of the length of the sidereal year.

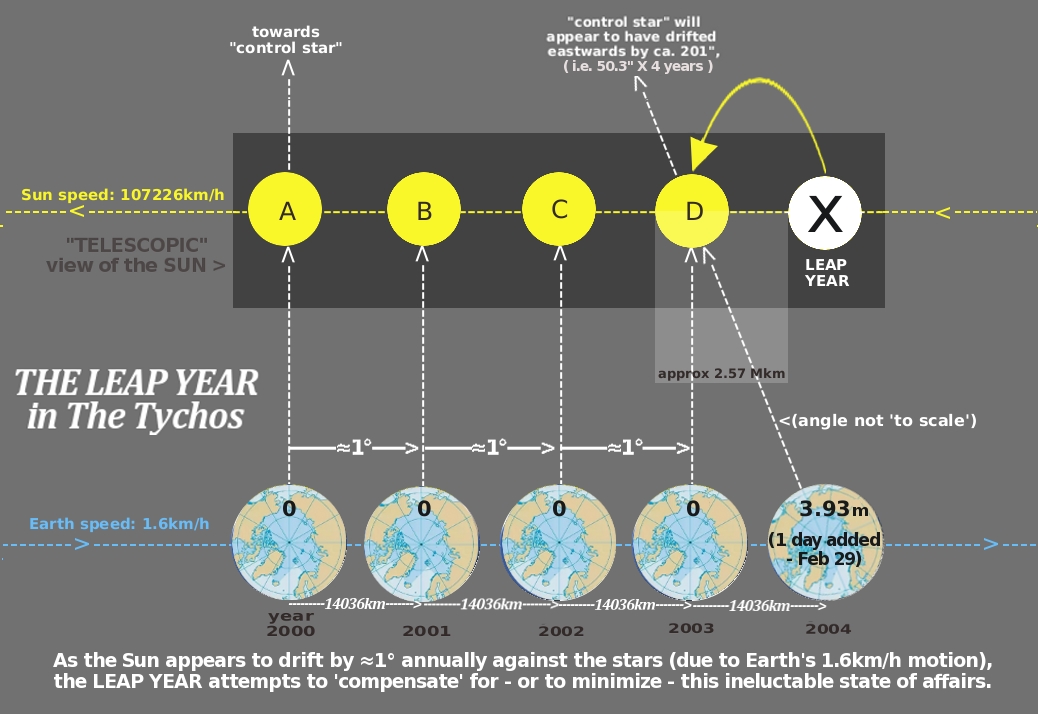

HOW FEBRUARY 29 "ADJUSTS" FOR EARTH'S MOTION AROUND ITS PVP ORBIT

Every solar year (of 365.2425 days), we see the Sun seemingly 'slipping westwards' against the starry background by about 1 minute (of RA). In four years, this would add up to an apparent 'solar westward drift' of about 4 minutes (or more precisely 3.9316 min). Therefore, every four years - i.e. every 'leap year' - an extra day is added (February 29) in order to try and 'compensate' for the Earth's motion around its PVP orbit.

As seen from the Earth, the subtended length of a 3.93 min "slice" of the Sun's orbit translates into a distance of about 2 566 300 km, because:

3.9316 min = 0.2730277% of 1440 min (our 360° celestial sphere) - and 0.2730277% of 939 943 910 km (the Sun's orbital circumference) ≈ 2 566 300 km

As it is, 2 566 300 km is just about the distance covered by the Sun during one sidereal day (107266 km/h X 1436 min ≈ 2 566 276 km).

Now, each day the Earth's axial rotation "ticks" (counter-clockwise) by about 3.93 min as it "follows" the Sun's (counter-clockwise) yearly orbit around us. Note that 1436 min (i.e. one sidereal day) divided by 365.2425 days (i.e. one solar year) = 3.93 minutes. Hence, by adding one extra day to our calendar every four years, we are in fact 'letting the Earth rotate' by an extra 3.93 minutes - while the Sun will move eastwards in our skies by an extra 2.566 Mkm or so.

As always, a picture is worth more than a thousand words - so hopefully my below conceptual graphic may help clarify the leap year issue:

As can be verified at the TYCHOSIUM simulator, the Sun was observed at the below celestial longitudes (RA) on June 21 in the years 2000 through 2004. We see that the Sun 'slips backwards' by about 1 minute each year - only for the leap year to 'push it forward' again by about 4 minutes:

2000-06-21: RA 06h01m42s (leap year)

2001-06-21: RA 06h00m41s

2002-06-21: RA 05h59m40s

2003-06-21: RA 05h58m39s

2004-06-21: RA 06h01m50s (leap year)

To wit, the Sun appears to "retrograde" by 1 minute each year - only for the leap year to 'reset' its original, apparent celestial position at virtually the same longitude in the sky. February 29 thus adds another 3.93 minutes to Earth's counter-clocwise rotation vis-à-vis the Sun. Interestingly, in 3.93 minutes, the Sun (moving at 107226 km/h) will cover some 7023 km - which is just about the distance that Earth covers in six months (7018 km). We may thus reasonably infer that our earthly clocks & calendar calculations have been calibrated so as to try and 'compensate' for the TYCHOS model's proposed annual displacement (14036 km) of the Earth around its PVP orbit.

One could say that the "leap day gimmick" (i.e. the addition of February 29 every four years or so) is a 'vain combat against the General Precession', or an attempt to counter the slow yet inexorable motion of the Earth around its PVP orbit. The reason for its existence in our calendar is primarily due to the wish of 'stabiizing' the recurrence of our (mostly religious) festivities and anniversaries. Easter, for instance, was a problem back in the days - as the Julian calendar (which took effect on January 1st, 45 BCE) had made its recurrence 'slip' by about 10 days or so. Thus, the Gregorian calendar was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII - and is still the one we use today. However, it is now widely recognized that even the Gregorian calendar count will prove to be problematic in the future.

"Experts note that the Gregorian calculation of a solar year - 365.2425 days - is still not perfect, and thus another correction will be necessary. Thankfully, the Gregorian calendar is only off by about one day every 3,030 years, so mankind has some time before this becomes a problem". "5 Things You May Not Know About Leap Day" - History.com

The question of the "true" and exact duration of our solar years is therefore, still today, far from settled. This should not come as a surprise though, since this world's scientific community still believes that the Earth revolves around the Sun and have never, of course, taken into account Earth's motion around its PVP orbit - as posited by the TYCHOS model.

THE 33-YEAR CYCLES OF THE SUN, MOON - AND MARS

The above-quoted book by Robin Heath goes on to mention a peculiar 33-year period under which the Sun will return rising in the 'same place':

"Over longer time periods than four years one gets the chance to obtain the length of the year with even more accuracy, by observing certain key years when the Sun rises precisely behind a foresight, stone marker, or notch in a distant mountain peak, a perfect repeat solar cycle. The best of these occurs after 33 years, 12053 days or sunrises. This is a staggeringly accurate repeat cycle and, remarkably, seems to have been known since prehistoric times. "Sun, Moon & Earth" - by Robin Heath

As it is, there is also a 33-year 'relationship' between the motions of the Sun and our Moon:

"The Time Period of Lunar and Solar Years. A lunar year has approximately 354 days. A solar year has 365 days. This leaves an 11-day difference between one solar year and one lunar year, resulting from the difference in their definitions. The term epact describes this specific time difference. Over the course of 33 years, there will be a lag of one year between solar and lunar calendars because of the successive epacts." "The Difference Between Solar & Lunar Years" - Sciencing.com

Interestingly, as viewed under the TYCHOS model's paradigm (what with Mars being the Sun's binary companion), Mars also has a distinct 33-year "cycle" of sorts - during which it moves from apogee (farthest from Earth) to perigee (closest to Earth):

Under the heliocentric model, these multiple "33-year correlations" (between the Sun, the Moon and Mars) would seem quite mysterious, for why would even Mars exhibit any sort of resonant (or 'commensurate') period in relation to the motions of the Sun and the Moon?

Let's now have some fun with numbers and see how this 33-year period would 'fit into' the TYCHOS' proposed duration for the "Great Year" (i.e. 25344 solar years). In 25344 years, there would be precisely 768 such periods of 33 years (because: 25344y / 33y = 768y). As expounded in Chapter 16, our Solar System seems to be 'regulated' by the number "16" - and its multiples. So let's see: 768 / 16 = 48 (which is of course 3 X 16). Whatever the significance of this (perhaps it is all coincidental?), it would nonetheless seem to support the exactitude of the TYCHOS model's proposed 25344-year duration of the "Great Year'.

The Tychosium simulator's secular accuracy

Before proceeding to chapter 20 ("Understanding the TYCHOS' Great Year"), this may be a good time to address the following question:

"Does the Tychosium 3D simulator agree with other (Copernican) Solar System simulators - over very long periods of time?"

The answer to this question is 'yes and no'. The simple reason being that the various available Solar System simulators all (slightly) disagree with each other - over longer time periods. However, there is one particular simulator (the "JS Orrery") that is of particular interest to the Tychos model, because its graphic construct / layout is very similar to that of the Tychosium 3D simulator. Moreover, the man credited with providing the exacting ephemeride tables (i.e. the secular planetary positions) for the JS Orrery is none other than Paul Schlyter, a world-renowned veteran Swedish astronomer who - a few years ago - spent several months corresponding via e-mail with yours truly and Patrik Holmqvist (the computer-programmer of the Tychosium 3D simulator - and my closest collaborator). To make a long story short, Paul Schlyter was adamant that the Tychos model was utter poppycock - and that any simulator of the same was doomed to failure. At the time, the Tychosium 3D simulator was in its early stages of development; Schlyter was quick to jump on its imperfections and, after a few months of (the rather petulant sort of) dismissive critique, Schlyter ended up abandoning the debate, lamenting that it was "just wasting his time".

Well, a few days ago (early March 2022), I went back to the JS Orrery and compared its secular planetary motions with those of the now perfected Tychosium 3D simulator. The below two screenshots (from the Tychosium and the JS Orrery) show the relative positions of the Sun, Mars, Earth, Mercury, Venus and Jupiter on June 21, 1915 - in both simulators:

The below two screenshots (from the Tychosium and the JS Orrery) show the relative positions of the Sun, Mars, Earth, Mercury, Venus and Jupiter on June 21, 25344 - in both simulators:

As you can see, the two simulators remain in most excellent agreement - over a time span of more than 23 thousand years! Patrik Holmqvist and I are now satisfied that the Tychosium 3D machine is now at least as reliable (in predicting secular planetary positions) as any of the most popular heliocentric Solar System simulators. Best of all, the wondrous Tychosium simulator (unlike its heliocentric counterparts) also agrees with the observed planets-to-stars alignments - and that's what makes it very special!...